Contact

fiona.reid@slu.se, +46 18 67 3242, +46 72 2288689

Writing a winning proposal to secure funding for your research takes time, effort and consideration. However, you can learn and develop this skill throughout your career, and the SLU Grants Office are here to help you. We have gathered the most common advice and feedback that we give when we review draft proposals and offer it here as a series of general tips to help you write better applications. You can also find more in-depth advice on some specific elements of proposal writing on our ‘how to write a good proposal’ page.

There are a wide diversity of funders, each with their own objectives for funding specific research. Therefore, you must understand the funder you are targeting with your proposal. This is equally relevant for highly prescriptive (top-down) calls and more open (bottom-up) calls.

Familiarise yourself with the proposal template and thoroughly read the call text, guidelines and evaluation criteria. Then, re-read them as you write your proposal to refresh your memory and make sure you have understood all the details. In many cases, you can use the instructions for evaluators as a checklist to make sure that you address all relevant points.

Sometimes, it can be hard to assess whether it is the right time to apply. Ask your colleagues and the Grants Office for advice since they may have experience with the specific funder or the funding programme.

Start developing your proposal by creating a 1-page concept note based on a structure such as Aim > Objectives > Tasks > Impact, as described in the figure below. The terminology for these elements can differ between funders (e.g. purpose, goals, activities, significance); nevertheless, the logic of the elements and the relationship between them holds. This is a creative and flexible way to crystallise your project idea and decide on a suitable frame for your proposal.

You have now built your scaffold, and it is time for a creative challenge!

Design a self-explanatory figure (i.e. no caption) that tells readers what you will do in the project and the anticipated effect. The figure should be clear enough so that someone who is not necessarily an expert in your research area will understand what you will do and what it will lead to. A figure like this can work well to introduce your overall project concept to the evaluator.

This creative work might also help you to think of a good acronym or short name for your project. Since you must sell your project to the evaluator, it might help to give it an identity and refer to it by an acronym, rather than calling it “the project” or “this proposal”. Make sure your acronym relates to the topic of your project and is easy to pronounce! If your project is funded, this acronym will be a big part of the project’s identity and help people refer to you easily.

Make sure that you answer these six questions within the first few paragraphs of your proposal:

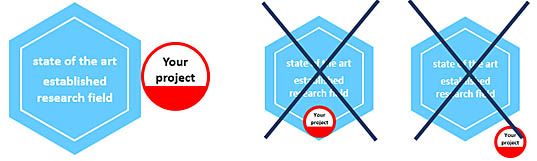

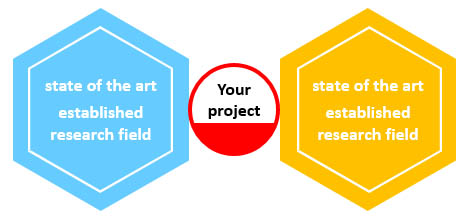

Position your project against the state of the art and show that you have adequate knowledge of the field. Make sure to clearly describe how your project expands the state of the art (ambition), that it pushes existing borders (novelty) and connects to the established research field (feasibility). Illustrate your expertise and suitability to take on this new challenge by highlighting how you and your project team (if applicable) have contributed to the state of the art. Make sure to calibrate this against the criteria set out by the funder in the call.

For interdisciplinary projects, present an ideal project where you help bridge two established research fields that are not interacting at present.

Telling evaluators what you will do is necessary but not sufficient. To underscore the feasibility of your project, you also need to outline the steps that you will take to achieve your objectives. The level of detail should be enough for the evaluator to understand what you will do, how and why. Avoid complex technical jargon, which may cause confusion, and explain terms that a non-expert may not be familiar with. What to include and emphasise depends on the field, but you should provide as specific information as possible about, for example, sampling and exclusion criteria; experimental techniques (and why those are appropriate); the types of data that you will collect; the approach that you will use for data analysis; and the expected results or outputs. However, you should, of course, calibrate this to suit the page/word limit and the funder’s guidelines.

You must also convince the evaluator that you, or your team, have the expertise required to achieve the project’s objectives. You can do this by describing the composition of your team, highlighting the core expertise of each individual or partner organisation, their roles in the project and how they will contribute to the overall work plan, e.g. areas of responsibility. You can also provide information on planned recruitments and key collaborators. Together with illustrating your contributions to state of the art, this is usually an efficient way of supporting the feasibility of your planned work.

In a collaborative project, if a funder asks you to involve organisations from different sectors across the value chain (sometimes referred to as the multi-actor approach), remember that all partners are equal. Do not separate academic/research partners from non-academic partners or stakeholders. Instead, develop and present your project as a team effort that involves co-creation, co-innovation and co-ownership of results.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of focusing all attention on developing your concept and methodology and leaving other parts of the proposal until the last minute. However, most funders will have quite broad evaluation criteria and require you to provide a range of specific information for the evaluators. Several key areas are common to most funders and calls, which you must address appropriately to make your proposal competitive and achieve a good score. You can find in-depth information and support on each of the following topics at the links below:

All projects carry some level of risk, so be transparent and highlight the risks that you have identified. A good project leader will recognise the importance of risk analysis and have a mitigation plan. Describe your Plan B if a particular risk occurs. This will be viewed positively by evaluators and show that you will be able to implement your project even though something potentially adverse happens. Be aware that not all risks can be identified from the start; ensure that you plan for continuous monitoring of risks, both those identified previously and the ones that are new.

Think about the style when you write your proposal and use an active voice as much as possible. For example, rather than writing, “Five case studies will be conducted, and the results will be used to develop new tools” (passive), try “SLU will conduct five case studies, and LUKE will develop new tools using the results” (active). In individual proposals, you can use statements such as “the aim of my research is…”, “I will…” or “I will lead my team to…” to indicate leadership and determination. The active voice is more engaging for proposals: it helps convey a sense of excitement and passion about what you want to do and why. Remember, you want to sell your idea to the reader.

You must also be specific in everything you write, for instance:

As much as you can, educate yourself about your audience and their background. Funders will often provide information about the composition of their evaluation panels, usually at least the research disciplines represented and whether evaluators from other sectors are included. In most cases, you must write the proposal so that specialists from your research field as well as those from other disciplines and generalists can understand the project concept. Use plain language to communicate your ideas clearly and explain any technical terms or acronyms when their use is unavoidable

Ensure that the different sections of your proposal have a good structure, the correct content and connect well to each other. Remember to double-check against the call text, funder’s guidelines and template, and confirm whether you have addressed all aspects that the evaluators will assess.

It is now time to send your draft for review. You could ask colleagues from a different research area and, in some cases, the Grants Office may also be able to help. Get in touch and find out. If the funder has provided the evaluation criteria associated with the call, then ask your peer to use them in their review. Aim to have your draft reviewed several times, incorporating any feedback, refining and improving your proposal with each version.

It is essential to take time to finesse your proposal before submission. The Danish Agency for Science and Higher Education conducted an analysis among evaluators of Horizon 2020 proposals and reported (in 2018) that evaluators look unfavourably at bad layout and poor readability. So, check your proposal text for typos, misspellings, grammatical mistakes, formatting issues and inconsistencies. It is a good idea to ask someone from outside your project team or consortium to do this: a fresh set of eyes is more likely to spot these kinds of mistakes. If possible, it may be beneficial to ask a native English speaker to proofread your proposal, and you can find language support on the staff web, including options for language revision of your text.

Take pride in what you do: never submit a proposal that is untidy and disorganised.

fiona.reid@slu.se, +46 18 67 3242, +46 72 2288689