Facts:

Link to Camilla's thesis.

Lindberg, Camilla, 2021. Markanvändning och kolbalans : beräkning av nettoutsläpp av koldioxid för SLU:s markanvändning. Avancerad nivå, A2E. Uppsala: SLU, Institutionen för mark och miljö

Earth Hour is held every year in March with the purpose to bring the world together, shine a spotlight on nature loss and the climate crisis, and to inspire more people to act and advocate for urgent change. Somebody working on energy monitoring using data collection, processing and visualisation of data on energy use, but also water and waste data is one of SLU's former students, Camilla Lindberg. She wrote her Master's Thesis on how the university's ownership of land affect carbon storage and emissions in different ways. Take part of an interview with Camilla and read about the results in her thesis.

You are a former student at SLU with a MSc in Environmental Science. We are also proud of having you as an intern at SLU Global a few years back. What are you up to these days?

– I currently work as a project manager and sustainability manager at a company called Mestro, we have a product for energy monitoring for property owners. So it is the collection, processing and visualization of data, then mainly energy use but we also collect water data and waste. Very much as a support in their sustainability work, with all the EU requirements on sustainability reporting, the demand for support and help has exploded. I have also recently started advising our customers on their energy and sustainability work as well. Very enjoyable!

Can you comment on what you found when doing your thesis work?

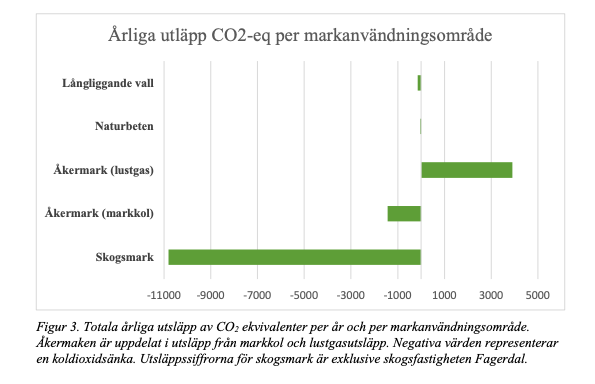

– What my work shows is that there are large carbon sinks in SLU's land. The forest holdings represent the largest carbon sink, but arable land and pasture land owned by SLU also report negative emissions.

– That the forest is an incredibly important component when it comes to balancing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is of course nothing new, but being able to quantify the amount for an organisation such as SLU in this way is important to really understand the role it plays in a larger context. The numbers speak for themselves.

– Also, one should not be satisfied with having a large forest holding and thus being able to say that one is doing enough to combat climate change, which SLU definitely is not! There are a range of measures available to increase carbon storage in the land use sector which I discuss in my paper. This is certainly something that the landowners I met are very interested in learning more about. It can often be simple measures that can increase sequestration a lot.

Thank you Camilla!

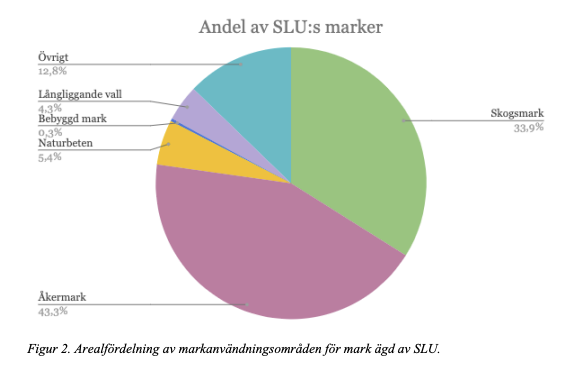

SLU owns forest land, arable land and pastures around Sweden that affect carbon storage and emissions in different ways - this report maps this carbon balance and calculates annual net emissions of carbon dioxide equivalents. Calculations for the carbon balance of SLU's land use have not previously been made and thus not included in the university's annual report on carbon dioxide emissions.

SLU's land use constitutes a net sink of carbon and stores just over 12200 tonnes of carbon dioxide each year. Carbon is mainly stored in the university's forest land, which alone accounts for net uptake of 10800 tonnes of CO2/year. Arable land, natural grazing land and longlying meadows together also account for net carbon storage. Emissions of nitrous oxide were calculated and the arable land has an emission of nitrous oxide in the order of 3900 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents per year. The reduction in land use is greater than SLU's total carbon dioxide emissions from other sectors, which means that universities could already now be considered climate neutral - which is otherwise the goal for 2027.

Recommendations regarding measures to increase carbon storage further emphasize production-increasing measures in forestry, increased grass cultivation on arable land and the use of catch crops and manure to increase carbon storage.

Lindberg, Camilla, 2021. Markanvändning och kolbalans : beräkning av nettoutsläpp av koldioxid för SLU:s markanvändning. Avancerad nivå, A2E. Uppsala: SLU, Institutionen för mark och miljö

SLU Global supports SLU's work for global development to contribute to Agenda 2030.

SLU Global

Division of Planning and Research Support

PO Box 7005, SE-750 07 Uppsala

Visiting address: Almas Allé 7

global@slu.se www.slu.se/slu-global

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us in social media.